Logging and auditing is one of the things that PostSharp is best at. It's the quintessential example of a cross-cutting concern. Instead of sprinkling logging code all throughout the app, you simply write a logging aspect in one place. You can apply it selectively or on the whole app.

You can get a lot of useful information with an aspect, but there are three popular categories:

- Code information: function name, class name, parameter values, etc. This can help you to reduce guessing in pinning down logic flaws or edge-case scenarios

- Performance information: keep track of how much time a method is taking

- Exceptions: catch select/all exceptions and log information about them

In contrast to logging/tracing, which is a technical issue, you can also use PostSharp for auditing, which is very similar to logging/tracing, except that auditing keeps track of information of a more business-nature. For instance, you may want to log parameter values to help fix bugs, and you may want to audit how many times a user performs a certain business activity (like a ‘deposit' for instance) in a given time frame. Typically a log may only need to write to a text file or very simple database table, while auditing may end up in a database table that's accessible in the application itself. Auditing may be closely tied to the authentication/authorization as well.

Let's use a simplified bank teller application. Let's say that this app can be used by live tellers or ATMs, and we'll simulate both with one simple WinForms UI. Also, the bank only has one customer for our purposes, and uses the following static class as the entire (very naive) business logic.

public class BankAccount

{

static BankAccount()

{

Balance = 0;

}

public static decimal Balance { get; private set; }

public static void Deposit(decimal amount)

{

Balance += amount;

}

public static void Withdrawl(decimal amount)

{

Balance -= amount;

}

public static void Credit(decimal amount)

{

Balance += amount;

}

public static void Fee(decimal amount)

{

Balance -= amount;

}

}

Of course, in a real app, you'd want to use a real service layer and dependency inversion instead of a static class. Maybe you'd use lazy loading dependencies (as mentioned in a previous post), but let's focus on the logging and auditing for now.

The app works very good, so long as you have very honest tellers and customers. Unfortunately, the CFO of this bank is on the verge of being fired, since millions of dollars have gone missing and no one can figure out why. She hires you, the humble PostSharp expert, and begs for your help in figuring out what's wrong. She wants you to put some code into place to keep records of all transactions and transaction amounts. You could write a bunch of boilerplate logging code and put it in every method in the business logic (only 4 methods in our case, but this would be many many more in a real application). Or, you could write one aspect and apply it to every method in the business logic right away. Since you won't be monkeying around in the actual business logic code, your aspect won't disrupt the app, and is relatively safe to deploy with minimal or no regression testing:

[Serializable]

public class TransactionAuditAttribute : OnMethodBoundaryAspect

{

private string _methodName;

private Type _className;

private int _amountParameterIndex = -1;

public override bool CompileTimeValidate(MethodBase method)

{

if(_amountParameterIndex == -1)

{

Message.Write(SeverityType.Warning, "999",

"TransactionAudit was unable to find an audit 'amount' in {0}.{1}",

_className, _methodName);

return false;

}

return true;

}

public override void CompileTimeInitialize(MethodBase method, AspectInfo aspectInfo)

{

_methodName = method.Name;

_className = method.DeclaringType;

var parameters = method.GetParameters();

for(int i=0;i<parameters.Length;i++)

{

if(parameters[i].Name == "amount")

{

_amountParameterIndex = i;

}

}

}

public override void OnEntry(MethodExecutionArgs args)

{

if (_amountParameterIndex != -1)

{

Logger.Write(_className + "." + _methodName + ", amount: "

+ args.Arguments[_amountParameterIndex]);

}

}

}

Note that CompileTimeInitialize is being used to get the method name and parameter names at compile time, to minimize the amount of reflection being used at runtime, and CompileTimeValidate is being used to make sure that there is an ‘amount' parameter to look at. If there isn't, it will generate a compiler warning (you could certainly change this to be an error if you wanted to prevent compilation entirely).

With that aspect in place, and a suitable place to store the auditing data (you could use a database or a logging framework--in this example I'm just using an in-memory collection), your application will start collecting data for the CFO's investigation in an unobtrusive way.

While that investigation is going, you suspect that there other problems with this system: it might not be the most robust of user interfaces, and after talking to the users, you learn that it tends to crash a lot. You could put try/catch blocks in every single UI method to see why it's crashing (this could be quite a lot in a large app). Or, you could just write a single aspect to handle the try/catch logging and recovery. Here's a very simple example:

[Serializable]

public class ExceptionLoggerAttribute : OnExceptionAspect

{

private string _methodName;

private Type _className;

public override void CompileTimeInitialize(MethodBase method, AspectInfo aspectInfo)

{

_methodName = method.Name;

_className = method.DeclaringType;

}

public override bool CompileTimeValidate(MethodBase method)

{

if(!typeof(Form).IsAssignableFrom(method.DeclaringType))

{

Message.Write(SeverityType.Error, "003",

"ExceptionLogger can only be used on Form methods in {0}.{1}",

method.DeclaringType.BaseType, method.Name);

return false;

}

return true;

}

public override void OnException(MethodExecutionArgs args)

{

Logger.Write(_className + "." + _methodName + " - " + args.Exception);

MessageBox.Show("There was an error!");

args.FlowBehavior = FlowBehavior.Return;

}

}

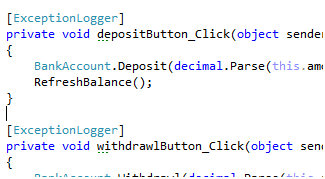

Once again, I'm using CompileTimeInitialize to cut down on the slow runtime Reflection. To use that aspect, I could decorate every method in the UI with it like so:

This isn't the worst approach--the exception handling/logging is still separated into its own class, but it's still repetitive and inflexible. Instead, let's just multi-cast out to all the methods like so:

// in AssemblyInfo.cs [assembly: ExceptionLogger(AttributeTargetTypes = "LoggingAuditing.BankAccountManager")]

If you have more than one class, you could instead set the AttributeTargetTypes to "LoggingAuditing.*" to hit every class in that namespace. Doing it this way means you don't have to put attributes on every single method.

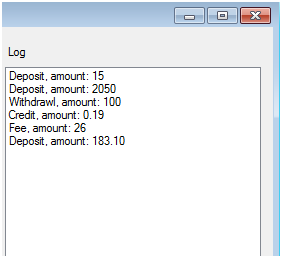

Once all this logging and auditing is in place, it should be fairly obvious to anyone reading the gathered information that two things have gone horribly wrong with the design of this app:

- Customers are allowed to withdraw negative amounts, and the less honest customers are taking advantage of this!

- Tellers that process a high volume of transactions make typos from time to time, but there is no checking being done on the input. If a teller enters "$5.19", for instance, decimal.Parse will throw an unhandled exception and crash the application.

With two very simple aspects, you've sussed out two glaring problems with the application, given the business users an audit trail of all transactions, and given the developers on your team an easy way to log and trace exceptions in production. As a consultant, you should recognize that a severely broken application in production like this indicates a deeper cultural problem with the development project team, but by using PostSharp to quickly diagnose these easily fixed problems, you will be on your way to building trust. You can spend this good will on introducing software craftsmanship principles and other bigger changes into the team.

Now, let's look under the hood a bit, and see what code PostSharp is actually generating, and give you some idea of the difference between the starter version and the paid version. Don't panic if you don't totally understand this yet; PostSharp is so easy to use that you might not ever have to open up Reflector to look at the generated code. But let's take a look anyway, just to get some insights into what PostSharp is doing.

Here is the "Credit" method without using PostSharp at all. As you can see, it's exactly what we would expect:

public static void Credit(decimal amount)

{

Balance += amount;

}

Now here's the "Credit" method after the starter version of PostSharp applies the TransactionAudit aspect. Remember that this code is only in the assembly, and your source code won't change at all.

public static void Credit(decimal amount)

{

Arguments CS$0$0__args = new Arguments();

CS$0$0__args.Arg0 = amount;

MethodExecutionArgs CS$0$1__aspectArgs = new MethodExecutionArgs(null, CS$0$0__args);

CS$0$1__aspectArgs.Method = <>z__Aspects.m11;

<>z__Aspects.a14.OnEntry(CS$0$1__aspectArgs);

if (CS$0$1__aspectArgs.FlowBehavior != FlowBehavior.Return)

{

try

{

Balance += amount;

<>z__Aspects.a14.OnSuccess(CS$0$1__aspectArgs);

}

catch (Exception CS$0$3__exception)

{

CS$0$1__aspectArgs.Exception = CS$0$3__exception;

<>z__Aspects.a14.OnException(CS$0$1__aspectArgs);

CS$0$1__aspectArgs.Exception = null;

switch (CS$0$1__aspectArgs.FlowBehavior)

{

case FlowBehavior.Continue:

case FlowBehavior.Return:

return;

}

throw;

}

finally

{

<>z__Aspects.a14.OnExit(CS$0$1__aspectArgs);

}

}

}

Again, don't panic! That might seem like quite a mess because of the odd names used, but it's really quite simple: the generated code is just wrapping your code (Balance += amount) inside of a try/catch, and sticking in calls to the overrides of the aspect. The only override actually used in this case is the "OnEntry" method (see line 7), but you can see where the other methods (like OnExit, OnSuccess, or OnException) would be called if you decided to override those methods too.

The above code is what's generated by the starter version of PostSharp. It's completely functional and works great, but as you might have noticed, since you're only using the OnEntry method of the aspect, there's a lot of unnecessary code in there (the try-catch loop, etc). For reference, here's what the paid version of PostSharp generates with its optimal code generation:

public static void Credit(decimal amount)

{

Arguments CS$0$0__args = new Arguments();

CS$0$0__args.Arg0 = amount;

MethodExecutionArgs CS$0$1__aspectArgs = new MethodExecutionArgs(null, CS$0$0__args);

<>z__Aspects.a14.OnEntry(CS$0$1__aspectArgs);

Balance += amount;

}

The paid version is smart enough to generate only the code that it needs to, and nothing else. If you are writing an application with heavy use of PostSharp aspects, it might be a good idea to use the paid version to help improve overall performance.

Anyway, despite the funny names used in the generated code, I hope that you're getting an idea of what PostSharp is actually doing under the hood, and the potential performance savings you could be gaining with the full version of PostSharp.

Matthew D. Groves is a software development engineer with Telligent, and blogs at mgroves.com.