The last consulting gig I was at, we were required to use an SOA framework to interact with enterprise-level data. This framework was SOA almost entirely in name only, completely home-grown, and was something of a misguided "pet project" of the chief of IT, insecure, built on some shaky technologies, and was created to solve a problem that was either non-existent, or solvable by much simpler means. My team was very frustrated by this framework, but as consultants, you sometimes have to learn to pick your battles, go for the easy wins first, build trust, and then gradually tackle larger problems. However, this can be a very slow process that takes years, depending on the organization.

In the meantime, we were stuck with this framework that didn't really work well with multithreaded apps (like, for instance, a web server), would often crash, and sometimes just wouldn't work at all. We had to build a working app on top of this mess, and since we're trying to build trust in the organization, we needed to ensure a certain level of reliability in the app that we were delivering. What we put together was an elaborate system of transactions, retries, error handling, and logging. This worked pretty well, and usually hid all the unreliable nastiness from the end user. However, to use this system, changes had to be made to every method that would touch the SOA framework. Soon after, I got tired of having to add this to every method, forgetting to add it only to see a bug get filed, having to remind others, violating single-responsibility over and over again, etc. I wondered if there was a better way, and that's when I first became interested in using AOP, and PostSharp specifically.

Enough ranting about bygone projects though: you can use PostSharp to improve transaction management, regardless of whether you're building an app on a brittle home-grown SOA or not. Here's an example of an OnMethodBoundaryAspect that will give you the basics of a typical transaction (i.e. start, commit, rollback):

[Serializable]

public class TransactionScopeAttribute : OnMethodBoundaryAspect

{

[NonSerialized] private ICharityService _charityService;

private string _methodName;

private string _className;

public override void CompileTimeInitialize(MethodBase method, AspectInfo aspectInfo)

{

_className = method.DeclaringType.Name;

_methodName = method.Name;

}

public override void RuntimeInitialize(System.Reflection.MethodBase method)

{

// in practice, the begin/rollback/commit might be in a more general service

// but for convenience in this demo, they reside in CharityService alongside

// the normal repository methods

_charityService = new CharityService();

}

public override void OnEntry(MethodExecutionArgs args)

{

_charityService.BeginTransaction();

}

public override void OnException(MethodExecutionArgs args)

{

_charityService.RollbackTransaction();

var logMsg = string.Format("exception in {0}.{1}", _className, _methodName);

// do some logging

}

public override void OnSuccess(MethodExecutionArgs args)

{

_charityService.CommitTransaction();

}

}

Really simple--there's nothing new here that we haven't seen in my other blog posts. Note that it's usually a good idea to rethrow the exception once you've handled the rollback, and that's done by default. Simply tag all the methods that need to take place in a transaction with [TransactionScope], and now you've saved yourself from writing the tiresome try/catch begin/commit/rollback code over and over with one simple aspect. And we've also gained a clean separation, and a great central place to put any logging code or special exception handling.

One thing that the above code doesn't address is the issue of "nested" transactions. In my example code, the Begin/Commit/Rollback transaction methods are just placeholders that don't actually do anything. In a production app, what you actually use to manage the transaction depends greatly on the underlying data access. If you are using ADO.NET connections like SqlConnection, ODBC, Oracle, etc, then you might want to use a TransactionScope (not to be confused with the name of this aspect) to make nesting easy (along with other things, like distributed transactions). If you are using some other persistence technology you may have to use a different API. However, remember to take the possibility of nested transactions into account (i.e. if there are two methods that both have the TransactionScope attributes applied to them, and one calls the other).

Now that we have a basic transaction aspect, go back to my original example: the service that I'm using will often fail and succeed inconsistently. What I need to add is a retry-loop: "if at first you don't succeed, try, try again." To do this, I can't use OnMethodBoundaryAspect anymore, I need MethodInterceptionAspect instead. Of course, I don't want to keep retrying forever, so I'll limit the number of retries with a hardcoded int value (or perhaps you'll want it in an App.Config or Web.Config file so you can change it without recompiling). I also know that a retry is only worth doing if a specific type of exception is thrown, say a DataException. On any other type of exception, it's worthless to retry (maybe the service crashed...again), so just log that exception for now and forget the retries (maybe in a production app you would want to automatically contact some on-call IT staff).

[Serializable]

public class TransactionScopeAttribute : MethodInterceptionAspect

{

[NonSerialized] private ICharityService _charityService;

[NonSerialized] private ILogService _logService;

private int _maxRetries;

private string _methodName;

private string _className;

public override void CompileTimeInitialize(MethodBase method, AspectInfo aspectInfo)

{

_methodName = method.Name;

_className = method.DeclaringType.Name;

}

public override void RuntimeInitialize(System.Reflection.MethodBase method)

{

_charityService = new CharityService();

_logService = new LogService();

_maxRetries = 4; // you could load this from XML instead

}

public override void OnInvoke(MethodInterceptionArgs args)

{

var retries = 1;

while (retries <= _maxRetries)

{

try

{

_charityService.BeginTransaction();

args.Proceed();

_charityService.CommitTransaction();

break;

}

catch (DataException)

{

_charityService.RollbackTransaction();

if (retries <= _maxRetries)

{

_logService.AddLogMessage(string.Format(

"[{3}] Retry #{2} in {0}.{1}",

_methodName, _className,

retries, DateTime.Now));

retries++;

}

else

{

_logService.AddLogMessage(string.Format(

"[{2}] Max retries exceeded in {0}.{1}",

_methodName, _className, DateTime.Now));

_logService.AddLogMessage("-------------------");

throw;

}

}

catch (Exception ex)

{

_charityService.RollbackTransaction();

_logService.AddLogMessage(string.Format(

"[{3}] {2} in {0}.{1}",

_methodName, _className,

ex.GetType().Name, DateTime.Now));

_logService.AddLogMessage("-------------------");

throw;

}

}

_logService.AddLogMessage("-------------------");

}

}

Yikes, this one looks a little scary! But don't worry, let's break it down into smaller, bite size pieces. CompileTimeInitialize, and RuntimeInitialize shouldn't look much different: they're just storing the class and method names, initializing the services we'll need, and initializing the maximum retries allowed.

For OnInvoke, let's break it down into the four possible scenarios that it handles:

- The method runs without exception and everything works. This is the happy path, and that's the block of code inside of the try { }

- The method fails with a DataException, and we haven't reached the retry limit yet. This is the code in the first part of the if/else inside the first catch { }.

- The method fails, and now we've exceeded the maximum number of retries. This is the code in the second part of the if/else inside the first catch { }.

- The method fails, but it's some unknown exception where a retry won't help. This is the block of code in the second catch { }

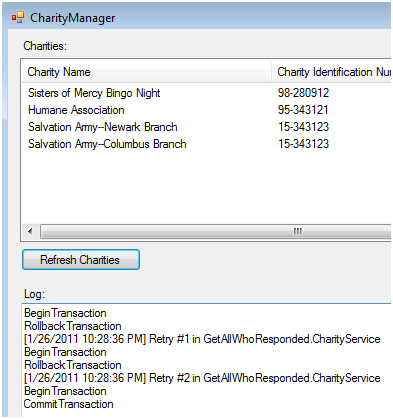

In my sample app, I've made a CharityService whose methods will fail almost 50% of the time due to a DataException, succeed 50% of the time, and throw a non-DataException exception 1-in-50 times. When you run the sample application, you'll be able to see in the log window how many retries are taking place (if any), along with the begins, rollbacks, and commits. Finally, the user will only see a MessageBox error message when the number of retries is exceeded, or when some non-DataException exception is thrown.

By using this aspect, you can give your application an improved level of robustness. The aspect code is getting large, but manageable. If it needs to get much more complex, it might be time to refactor: consider putting each case into its own class, and just use the OnInvoke method to establish a general flow.

The real-world example I gave at the beginning of this post is (hopefully) a rare case, but even the best of architectures can fail from time-to-time. You don't have to dread handling those situations when you are using PostSharp to implement SOLID principles in your application.

Matthew D. Groves is a software development engineer with Telligent, and blogs at mgroves.com.

Matthew D. Groves is a software development engineer with Telligent, and blogs at mgroves.com.