Soothsilver Initiative Tracker

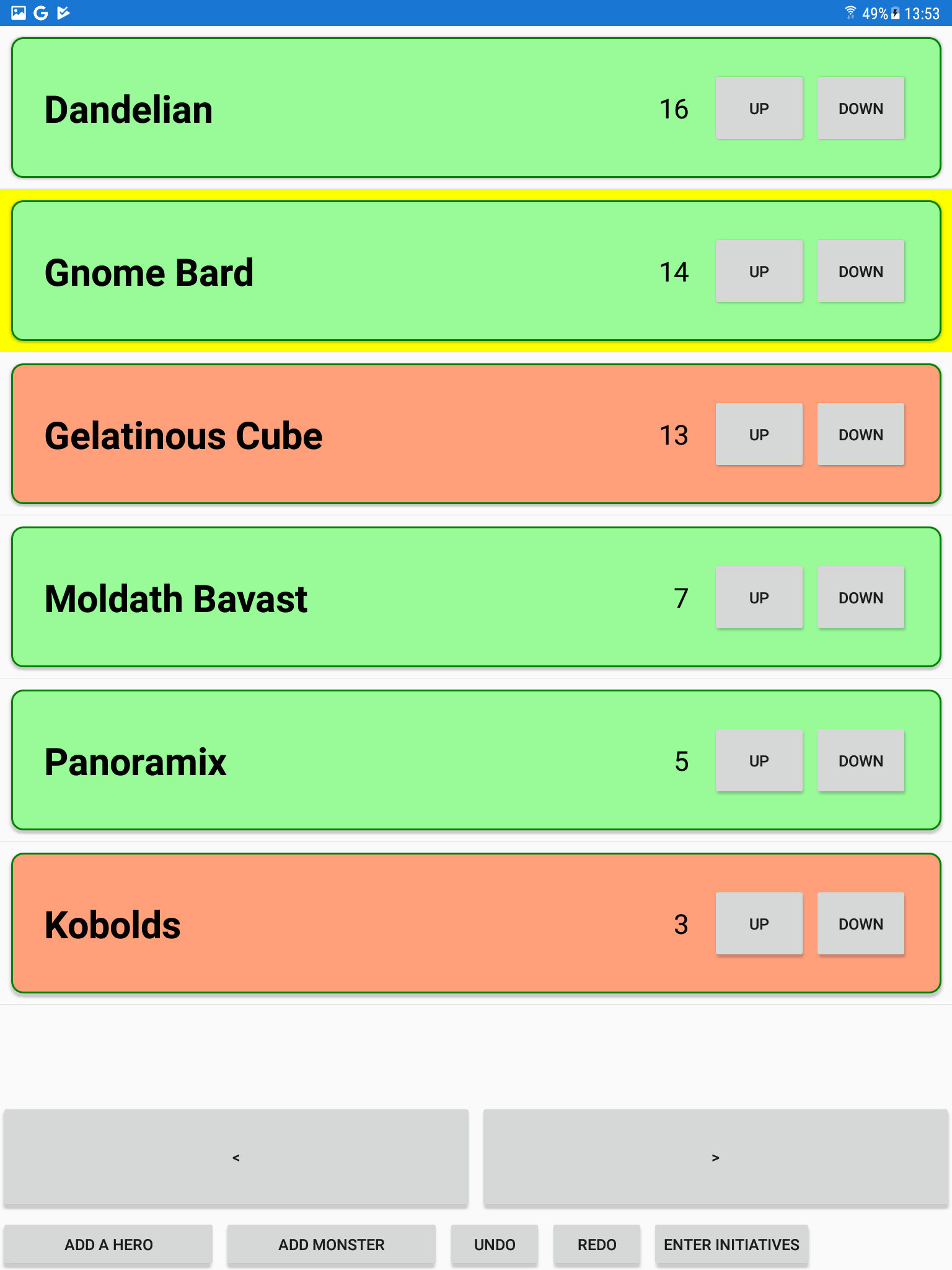

The app looks like this:

In pen-and-paper roleplaying games, such as Dungeons & Dragons, in combat, players take turns in the order of initiative: a number based on what each player rolls on a die. Because each player takes several turns in a combat, and the order of players is different each combat, playgroups make use of an initiative tracker to keep track of whose turn it is, who goes next and so on.

As you might expect, there are many initiative trackers on Google Play already. I know because I tried them all — but not one that matched all of my requirements exactly, so, of course, I rolled out my own :).

And it worked well — I made it within half a day (though the subsequent process of publishing it on Google Play took about as many hours again) — and our playgroup is still using it four months later.

I should mention that is entirely my own personal hobby project — I host in on my own GitHub (give me a star) and PostSharp as a company certainly does not provide support (but feel free to ask me). We don't even officially support Android at the moment, though as evidenced by this app, it generally works, including debugging.

Using Xamarin with XAML

I made some attempts at Android development before, using Java/Kotlin and native Android API, but I often got stuck and never created anything worth publishing. That's why this time I tried if maybe using C#/.NET would work better.

It did, curiously, but it still wasn't close to desktop development. You know how when you're developing a desktop application and you type in some code and press F5 and it immediately just runs? And how when you're developing a mobile application and you need to install several prerequisites and check manifests and set configuration options? That's still there, even when you're using Xamarin.

There's also the fact that everything is slower: the designer, the build, the transfer to your device or to the emulator, even the distribution process and upload to Google Play. I think if I had more experience, it would go faster, but I still found the entire process more complicated. Part of the reason why I don't create mobile games.

The user interface design, at least, was more familiar. I used Xamarin Forms with XAML design files and the paradigm is very similar to UWP and WPF so I created my screens quickly. Visual Studio now even supports live updates: I modified my XAML, saved the file, and the form on my device changed!

Of course, XAML also means INotifyPropertyChanged, the XAML solution to data binding.

INotifyPropertyChanged

I've used INotifyPropertyChanged in several projects so far and I still don't quite like it.

Personally, as far as binding values to user interface elements goes, my number one favorite approach is the low-level draw loop (as in XNA/MonoGame): you ask your model sixty times a second what are you supposed to draw and you draw that. That isn't an option in complex UI frameworks.

My next favorite approach is the one taken by JavaFX: you use special smart properties (wrappers) in your model and bind them among themselves. I find that clearer, less boilerplatey, but it's getting complex, especially with the larger elements like list views.

Regardless, Xamarin has XAML, and XAML means MVVM and INotifyPropertyChanged. Fortunately, this time, I have PostSharp.

PostSharp auto-implements everything about INotifyPropertyChanged. With it, I was able to reduce the interacting part of my model to this:

[NotifyPropertyChanged]

[Recordable]

public class Creature : INotifyPropertyChanged

{

public string Name { get; [ThenSave] set; }

public bool Friendly { get; set; }

public int Initiative { get; set; }

[SafeForDependencyAnalysis]

public bool Active

{

get { return MainPage.Instance.Encounter.ActiveCreature == this; }

}

[SafeForDependencyAnalysis]

public Xamarin.Forms.Color BackgroundColor

{

get

{

if (Friendly) { return Color.PaleGreen; } else { return Color.LightSalmon; }

}

}

...

}

PostSharp's solution to INotifyPropertyChanges is magic so I'll walk you through what's happening here.

The [NotifyPropertyChanged] attribute is a PostSharp attribute and it means "whenever any property of this class changes, raise a PropertyChanged event for that property". For the properties Name, Friendly and Initiative, it means the event is raised after some code uses their setter.

But what about the properties Active and BackgroundColor which are getter-only?

The property MainPage.Instance.Encounter.ActiveCreature is referenced via a static property (MainPage.Instance) so there's no way to react to its change from within the class Creature. What I do in this app is that I use OnPropertyChanged to manually raise the PropertyChanged event for the property Active for all creatures whenever the active creature changes. PostSharp can't help here because of the unfortunate way in which I set this up. What I should have done instead is add to the Creature class a reference to its parent Encounter, which removes the need to refer to a static property.

For BackgroundColor, the situation is different. The property's value depends only on another property of the same creature: whether it's friendly or not. PostSharp can determine this (it reads the IL code of BackgroundColor's getter and sees that it references the property Friendly) and makes it so that whenever the value of Friendly changes, a PropertyChanged event is raised also for BackgroundColor — and I didn't need to write any code.

The [SafeForDependencyAnalysis] attribute in my code sample is a signal to PostSharp that even though the code within uses static properties, it's okay and PostSharp shouldn't emit a warning. PostSharp normally emits the warning to tell the user "hey, I can't automatically raise events in response to changes of static properties; are you sure you're handling that yourself?". It's necessary even for BackgroundColor because it refers to Color.PaleGreen and Color.LightSalmon, and those aren't constants, they're merely static fields. (They are readonly, so maybe the warning isn't really necessary and we could look into suppressing it.)

Other uses of PostSharp

You may have noticed a couple of extra attributes in my code sample.

Those weren't strictly necessary but since I was using PostSharp already, I figured, why not go all the way.

[ThenSave] is a method boundary aspect I created. It means, "after this method completes, save all creatures on disk so they're not lost when the user closes the app". I could have done this instead:

private string _name;

public string Name { get => _name; set { _name = value; ThenSave.SaveEverything(); } }

Which would do the same thing, but I feel like the solution with the [ThenSave] aspect is prettier and if I needed it for more than one property, it would also help save lines of code.

The last attribute I didn't talk about is [Recordable]. This one is a built-in PostSharp attribute which means "I remember everything that happens to me; you can use undo/redo."

Normally, when you implement undo/redo, for each possible action the user can take, you create a triplet: what happens when you take the action, what happens when you undo it, and what happens when you redo it.

PostSharp's undo/redo makes use of the fact that most of the time, everything that these actions do is just changing the values of some properties. So, whenever you change the value of some properties of a [Recordable] object, the object remembers it and it's added to the undo stack which I exposed with the Undo and Redo button on screen.

I also marked the list of all creatures (the class Encounter) as [Recordable] as well. That way, if I first change the name of one creature in the encounter and then another, both changes are made to the same undo stack and can be undone in turn by the same button.

I suppose the app didn't really need an undo/redo functionality. Most initiative trackers on Google Play don't have one. But with PostSharp, it cost me very little to add it and it actually proved useful, especially since typing is more time-consuming on tablets so undoing a mistaken name change rather than retyping the original name helps speed up gameplay.

Publishing on Google Play

I didn't technically need to publish the game: I mostly wanted it for myself and the build that Visual Studio placed on my tablet was good enough. But publishing seemed simple enough and maybe in the future I'll want to create a true game and this could be a trial run.

It wasn't actually all that simple. The Google Play Console, the online app that you use to upload and manage your Google Play games, has about twenty pages that you can fill in and about half of them are mandatory.

Uploading the binary itself failed several times for me when I checked the wrong checkboxes when creating the distribution build in Visual Studio. Visual Studio has a feature that allows you to upload your build to the Play Console from Visual Studio, but it broke at some point in the past and doesn't seem to work anymore. Still, for every problem I faced, there was a forum thread somewhere on the internet that pointed me in the right direction.

The cost of creating a Google developer account was just $25 and it's a one-time fee that I don't need to pay for future apps.

Whenever I made a change to the game data, either uploading a new build or even fixing a typo in the store listing description, it required a new verification from Google, which seems to be manual at least the first time around: it took about a week to get my first version approved (but subsequent approvals were faster). I didn't actually talk or chat with a human at any point.

Overall, it was a good experience, though I recommend that you do this on a powerful computer (because creating the distribution build is slow) and with good internet (because the distribution package for Google Play is large and you need to upload it).

Conclusion

I'm happy with how my app turned out.

I used the free Essentials edition of PostSharp (more than enough for a little app like this). As an employee, I had access to the full Ultimate edition but I didn't need it. (You may also be eligible for a free Ultimate license.)

If I didn't use PostSharp, I certainly wouldn't have implemented Undo/Redo and my Encounter and Creature classes would increase in size and complexity a bit but with a bit of refactoring, it would still be quite manageable, I think. That said, XAML is a technology where PostSharp shines and I certainly prefer the current code than what it would have been without PostSharp.