In this blog post, we present PostSharp Logging, a .NET library for automatic detailed tracing, and NXLog, a log management system for collecting, processing and forwarding log data, and show how you can use these tools in your applications.

We’ll consider the following scenario. You are developing a large product consisting of ten different applications that communicate with each other over an enterprise service bus or other means. Each application (service) is a standalone program, most are written in C# but some might not be .NET at all. When something happens unexpectedly in such a complex system, how do you make sense of it?

Automatic detailed logging with PostSharp

First, you’ll need logs. You want to know what was happening in each application when an unexpected situation occurred.

Traditionally, you would have your applications create logs by sprinkling the code with logging statements: at the beginning of some methods, in catch blocks, and elsewhere. But you never quite know what information you will need and it is easy to forget this kind of logging.

PostSharp Logging can help here. When you add PostSharp Logging to your application or library, you designate some methods as being logged. You can do it by annotating the method with the [Log] attribute, annotating a class to log all methods in it, or you can use regexes or even C# code — executed at build time — to designate a large number of methods as logged at the same time.

The methods will then print their name, along with parameters and return values, when they’re entered or exited.

In our example app, we’ll use [assembly: Log] to log all methods and we’ll use the following configuration at the beginning of our main method to send all logging events to a local file:

Log.Logger = new LoggerConfiguration()

.MinimumLevel.Debug()

.WriteTo.File("single.log", outputTemplate: "{Timestamp:yyyy-MM-dd HH:mm:ss}[{Level}] {Indent:l}{Message}{NewLine}{Exception}")

.CreateLogger();

LoggingServices.DefaultBackend =

new SerilogLoggingBackend(Log.Logger)

{

Options =

{

IncludeExceptionDetails = true,

IncludeActivityExecutionTime = true

}

};

This configuration causes would cause all methods in the app to emit logging lines so you’ll end up with a file looking like this:

2020-11-09 13:51:39[Debug] Program.AcceptRequest(EnterpriseApp.Request = { {Request; Index:9} }) | Starting.

2020-11-09 13:51:39[Debug] Request.get_Index() | Starting.

2020-11-09 13:51:39[Debug] Request.get_Index() | Succeeded: returnValue = 9, executionTime = 0.01 ms.

2020-11-09 13:51:39[Information] | Processing request 9.

2020-11-09 13:51:39[Debug] Program.Enhance(EnterpriseApp.Request = { {Request; Index:9} }) | Starting.

2020-11-09 13:51:39[Warning] Program.Enhance(EnterpriseApp.Request = { {Request; Index:9} }) | Overtime: executionTime = 527.79 ms, threshold = 500 ms.

2020-11-09 13:51:39[Debug] Program.Persist(EnterpriseApp.Request = { {Request; Index:9} }) | Starting.

2020-11-09 13:51:39[Information] | Persisted.

2020-11-09 13:51:39[Debug] Program.Persist(EnterpriseApp.Request = { {Request; Index:9} }) | Succeeded: executionTime = 0.05 ms.

2020-11-09 13:51:39[Warning] Program.AcceptRequest(EnterpriseApp.Request = { {Request; Index:9} }) | Overtime: executionTime = 528.04 ms, threshold = 500 ms.

(In a real scenario, you would only apply [Log] to some methods or you would specify exclusions.)

Collecting the logs

We can do this for each of our services but now each service has its own log file, and possibly each service lives on a different computer, so where do we go to when we need to read the logs?

Here it might be useful to collect the logs from all the services and dump them into some common storage log server. We will use NXLog for this. NXLog is a multi-platform log forwarder, bringing capabilities to collect logs from a variety of sources, and forwarding them to different collectors. In our case, it will run on each of our computers and transmit logs from each service’s “single.log” file to the NXLog instance at the common storage computer, using TCP/IP.

In addition, we’ll have the local NXLog add the computer’s name to each of the log messages so that we know where each log message in the common storage comes from.

We’ll use this nxlog.conf configuration:

define HEADERLINE_REGEX /^(\d{4}-\d{2}-\d{2}\s\d{2}:\d{2}:\d{2})(\[\S+\])\s+(.*)\|\s+(.*)/

define EVENTREGEX /^(\d{4}-\d{2}-\d{2}\s\d{2}:\d{2}:\d{2})(\[\S+\])\s+(.*)\|\s+(.*)/s

<Extension multiline>

Module xm_multiline

HeaderLine %HEADERLINE_REGEX%

</Extension>

<Input input_file>

Module im_file

File "C:\\app\\logs\\single.log"

InputType multiline

<Exec>

$Hostname = hostname_fqdn();

if ($raw_event=~%EVENTREGEX%)

{

$EventTime = parsedate($1);

$Severity = $2;

$Method = $3;

$Message = $4;

}

$raw_event = $EventTime + $Severity + " <" + $Hostname + "> " + $Method + "| " + $Message;

</Exec>

</Input>

<Output output_tcp>

Module om_tcp

Host 10.0.1.22

Port 516

OutputType Binary

</Output>

<Route Default>

Path input_file => output_tcp

</Route>

This means that the local NXLog instance will monitor single.log for changes and each time a new row is added, NXLog will read it, transform it, and send it to our server at 10.0.1.22.

On the storage server, we’ll gather the logs from each TCP connection and dump them into a local rolling file using this configuration:

<Extension _fileop>

Module xm_fileop

</Extension>

<Input input_tcp>

Module im_tcp

Host 0.0.0.0

Port 516

</Input>

<Output output_file>

Module om_file

File "/opt/nxlog/var/log/server_output.log"

<Schedule>

Every 1 hour

<Exec>

if file_size(file_name()) >= 10M

{

file_cycle(file_name(), 7);

reopen();

}

</Exec>

</Schedule>

</Output>

<Route Default>

Path input_tcp => output_file

</Route>

This configuration means that we accept input data from all network interfaces at port 516/TCP and write them to a rolling log file — and there are at most 7 log files of 10 MB max each.

Now, when an unexpected situation occurs, you can search for the timestamp in these common files and you have access to what was happening in each service.

Reporting to Kibana

But we can go further.

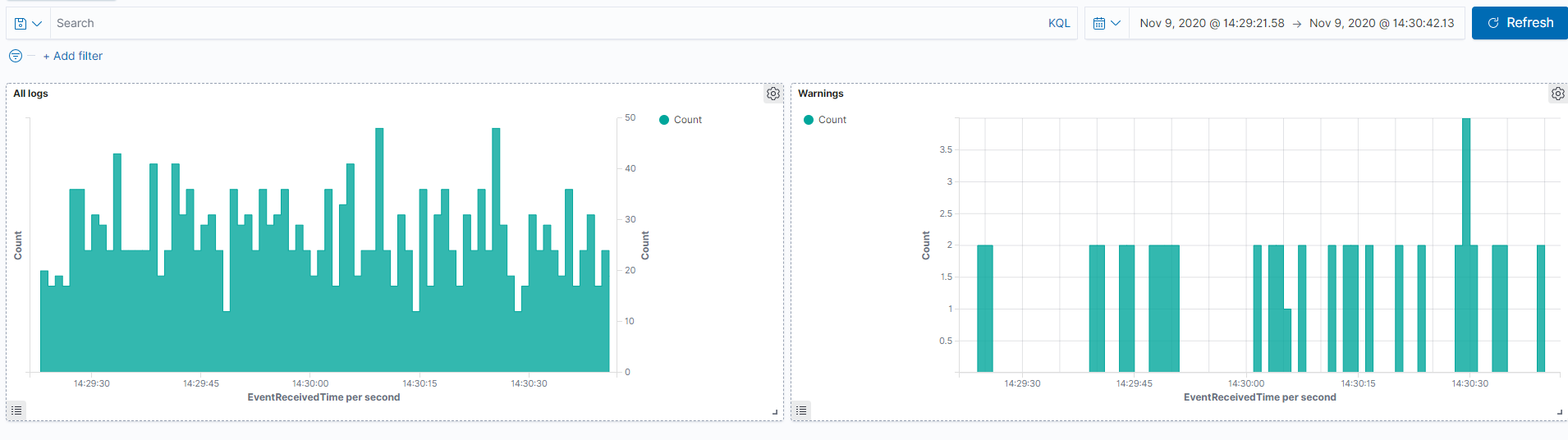

A common requirement is to be able to monitor the health of running services. Our infrastructure already allows us to add some health monitoring easily by pushing log messages to a database such as ElasticSearch and display them in a Kibana dashboard like this:

The chart on the left represents all logs and the chart on the right warnings only. PostSharp automatically escalates log messages to warning level if a method ends with an exception, or when its execution time exceeds some allotted threshold time.

NXLog Enterprise Edition provides om_elasticsearch, an efficient built-in module to send data to ElasticSearch (more information in the NXLog Documentation) but even using the Community Edition, we can use the HTTP module om_http for such a use case with the following configuration:

<Output output_http>

Module om_http

URL https://localhost:9200/

ContentType application/json

<Exec>

if $raw_event =~ /^(\d{4}-\d{2}-\d{2}\s\d{2}:\d{2}:\d{2})\[(\S+)\]\s<(\S+)>\s+(.*)\|(.*)/s

{

$EventTime = parsedate($1);

$Severity = $2;

$Client = $3;

$Method = $4;

$Message = $5;

}

set_http_request_path( "my_index/_doc" );

rename_field("timestamp", "@timestamp");

to_json();

</Exec>

</Output>

In the same file, we’ll need to change the route to output to both targets: the file and Elasticsearch.

<Route Default>

Path input_tcp => output_file, output_http

</Route>

This configuration takes the data coming in over TCP and sends them both to the collected log file and also sends it as JSON objects to Elasticsearch API, registering each log line as a new document (you can of course filter this to send warnings and errors only).

Conclusion

We imagined a complex enterprise application running across multiple servers, and created a system that produces, gathers and presents logs, with only a reasonable amount of work needed.

We used PostSharp Logging and NXLog Community Edition but we have barely scratched the surface of what is possible with these tools.

You can learn more about the possibilities offered by PostSharp Logging and NXLog at their official websites.